Policy Implications

The identification of suitable intervention pathways requires an appreciation of how and why food is consumed, and the design of initiatives that are nutrition sensitive or nutrition specific. These initiatives involve multiple actors throughout the entire food environment. The ‘food environment’ refers to the physical, economic, political and socio-cultural context in which consumers engage with the food system to make their decisions about acquiring, preparing and consuming food.

On the supply side, initiatives might undertake innovations to increase the nutritional value of food. This can be done, for instance, through: securing shorter value chains, adopting fortification (addition of valuable micro-nutrients to foodstuffs), improving storage of perishables, and reducing use of food additives or hydrogenated fats.

On the demand side, choices about food consumption and dietary patterns reflect food availability, aspiration, affordability and acceptability. The decision matrix therefore depends upon whether consumers grow their own food, as well as on their income, information – and any constraints of time or social and religious custom. Lack of access to food – in the dual sense of physical and economic access –increases the risk of undernourishment, as well as of obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases. Longer work hours, urbanisation, and the availability of processed and fast food each contribute to poor nutritional and environmental outcomes. Consumer behaviour may be influenced through interventions known as ‘choice architecture’, advertising restrictions, or through ‘agentic’ interventions (incentives, ‘sugar taxes’, education programmes, food labelling) or food-based dietary guidelines.

Food-based dietary guidelines have been shown to reduce social inequalities in diets in developing countries when targeted towards disadvantaged groups, but their potency may be limited if ‘healthier’ food is less energy intensive, less tasty or more expensive. Some fruit and vegetables, for example, can be cheap but are low in calories. Others can be rich in Vitamin A but too expensive.

South East Asia has seen the sharpest increase in overweight populations with a 128 percent increase since 2000. These regional and national challenges to meeting SDG 2 indicate the need for a comprehensive food and nutrition policy, within a food systems framework, which has the scope to increase spending and integrate nutrition into healthcare provision.

ASEAN’s policy response has broadened from the 2014 WHO Action Plan to Reduce the Double Burden of Malnutrition (2015–2020) to the ASEAN Leaders’ Declaration on Ending All Forms of Malnutrition at the 31st ASEAN Summit in 2017. The 2014 plan initiated the elevation of nutrition to the development agenda: the promotion of breastfeeding; the strengthening of legal frameworks supporting healthy diets; the improvement of nutrition services across public health programmes; and the provision of financial incentives to adopt healthy diets. The case of breastfeeding is a case in point, with only 30 percent of children being exclusively breastfeed at six months, and it is estimated that there are annually 12,400 child and maternal deaths that could be attributed to inadequate breastfeeding. There is urgent need for putting in place effective breastfeeding strategies across the region to be able to harness the health benefits for infants and young children.

While the 2017 ASEAN Declaration does reaffirm a high level of political commitment toward a multi-sectoral collaborative approach across agriculture, public health and nutrition and social welfare, there needs to be explicit and detailed linkages made between types of food, and the impact for nutrition, for different demographic groupings (infants and mothers in the case of breastfeeding). In March 2018 the Philippines led the formulation of a framework to implement the Declaration. This is a valuable opportunity to have a more integrated food and nutrition approach to health; it builds on the previous collaboration with UNICEF, when ASEAN collated examples of healthy diet promotion in the Regional Report on Nutritional Security in ASEAN. These include Nutrition-sensitive interventions to increase the production and sale of nutrient-rich foods and nutrition-specific interventions to increase consumption of fruit and vegetables, reduce consumption of free sugars, salt and fats and to encourage dietary diversification. These examples serve as indicators of the types of the things that work, but should not be interpreted as blueprints. They can be used as ingredients of success, but their precise make-up should be subject to collective and contextual design.

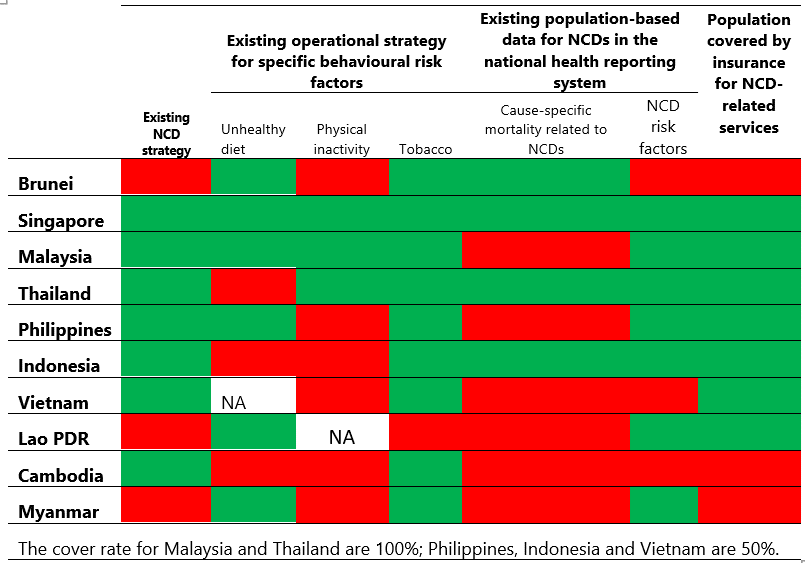

National capacities for control of NCDs in ASEAN

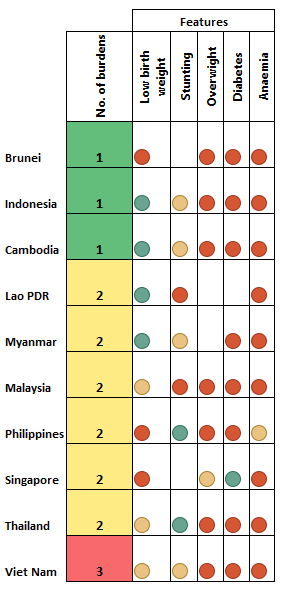

Malnutrition burdens in ASEAN

The ‘pillars of success’ in these models appear to be collective action, plus a portfolio of measures to make behavioural change easier: either fortification of a staple food (so diets remain unchanged) or monetary or non-monetary incentives to change, such as conditional transfers. A recent analysis found that there are also shortcomings in food supply chains, and the losses and waste in perishable products such as fruits and vegetables is higher than for cereals and pulses in southeast Asia. The need for farmer production organisations or other types of collective action to overcome the individual inability to improve the logistics of food supply is crucial to improving food affordability and use.

The absence of universal blueprints for improving nutrition does not stop lessons from being learned from global, as well as regional, examples – even if they are failures. The essential point is to identify how and why success or failure came about. One approach – Double-Duty Actions (DDA) – tries to identify common drivers, including: early life nutrition, diet diversity, food environments, and socioeconomic influences. These drivers can be used to develop a simple framework of factors to be considered when addressing multiple forms of malnutrition, in order to identify the feasibility and risks of adapting measures focused on undernutrition to address over-nutrition.

The logic of such an evidence-based approach highlights the existence of major data gaps on nutrition indicators: particularly the degree of disaggregation by location and social cohort. It also suggests a re-evaluation of modes of implementation. Rather than focusing solely on the short-term behaviour of an individual, policy design should look across the life-long behaviour of groups; policy must pay attention to the inter-generational aspects of healthy systems, within a capability model that encompasses the motivations and constraints under which nutritional decisions are made.

Evidence suggests a need for an integrated and multi-pronged policy strategy to address immediate, as well as long-term, underlying causes of malnutrition for maternal, infant and child health. The WHO formalised concerns about the vulnerability of groups through the establishment of the World Health Assembly (WHA) implementation plan in 2012. The case of wasting among children is a case in point, where the WHA goal is to reduce wasting to less than five percent in childhood. The ASEAN region, where this figure is around 10 percent, would need to reduce the prevalence of wasting by half to meet this goal. The targeting of health services (such as antenatal care, feeding practices and early childhood growth monitoring programmes) and explicit linkages with food and nutrition programmes brings together health systems and food systems. This approach could also assist in more innovative thinking regarding, for example, social safety nets; the redesign of school feeding programmes; and the scaling up of nutrition-sensitive agriculture programmes.

Efforts to improve food consumption and nutrition are likely to benefit from a Foresight study to assist in policymaking. This approach carefully weighs the full range of expertise – from agriculture, environmental science, public health, behavioural economics and social welfare – required to produce comprehensive and joined-up strategies for improving nutrition and health across population groups. It also embraces participatory forms of development thus helping to ensure that the attitudes and insights of consumers, small scale-farmers and other relevant stakeholders are considered and included.

A Foresight approach to evaluating nutrition will first identify key drivers (including risk factors) that govern nutrition outcomes. These are likely to include some or all of the following: wealth disparity and demographic transitions (where wealth can paradoxically create new forms of nutritional challenge, especially obesity); insecure livelihoods and stunting linked to malnutrition; calorie sufficiency with nutrient insufficiency etc; cultural aspirations – lifestyle choices as wealth increases; the role of education in imparting knowledge about optimal nutrition; the role of regulation in curbing or promoting certain food standards and dietary composition, especially in relation to sugar; processed food composition; health and safety standards around food preparation, packaging and sales; the role of supermarkets and big business – their soft power in influencing food choices; the role of advertising and lobbying in creating poor dietary outcomes; the impact of urban design in promoting lifestyles for healthy outcomes (cycling, walking, parks, playgrounds, street-lighting, street safety, social norms about who can walk safely during cooler times of the day). From these complex drivers and their connections and interactions, a set of scenarios can be developed for deeper exploration, drawing on expertise in all the diverse disciplines, societies and policy sectors implicated in the challenge. Malnutrition and obesity both exist in different parts of ASEAN society. Malnutrition has been a global concern for decades, and yet it persists. Obesity is also proving to be one of the most challenging dangers to human health, as wealth and urbanisation increase: generating the term ‘obesogenic society’. Its causes are complex, and tackling obesities is recognised as a complex and multi-faceted process.

Finally, all scenarios developed in a Foresight approach can be subjected to the analysis of ‘pro-active’ versus ‘reactive’ interventions, and ‘collective’ versus ‘individual’ responsibility. Thus, a complex, layered study can produce recommendations for policy information that address many different circumstances and locations, whilst creating a cohesive and coherent regional strategy for the next fifty years or so.

A foresight study can set the framework for charting the evolution of consumer behaviour over the life-course or across generations. It can also model supply-side factors, such as climate change, land use or water management, that affect the quality and quantity of food production. Foresight can help to weigh the feasibility and risk associated with specific policy options and interventions.

The combination of measures to address the immediate causes through nutrition-specific interventions – such as the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Essential Nutrition Actions (ENA) – and nutrition sensitive ones can create a virtuous cycle of resilient and sustainable health outcomes. Due to considerations of scope, we consider only two key aspects of this: access to health coverage and to water and sanitation.