‘Human development’ encompasses the dimensions of health and social welfare, and emphasises the social development aspects of human life. It is an advance over the more traditional understanding of ‘human capital’ theory that health is a form of private investment. The current thinking in human development recognises that ‘being healthy’ is a human condition that is not equally accessible to all individuals. Improvement in life expectancy, and the ability to remain in good health, varies across the world; the UN’s Human Development Index, includes life expectancy and other health metrics.

A society’s ability to ensure a socially-just health system is indicated by the distribution of health provision across all sectors of society: whether with regard to rural or urban location, or by age as a youth entering the work force or a recently retired pensioner, or back on income levels as wealthy or underprivileged; and also by the availability of social protection measures for those who are in conditions of ill health. There are also culturally contingent aspects, such as the marginalisation of indigenous groups who may live in distant rural or forest locations, making it difficult to access health provision.

Social determinants result in inequalities that can impact on mental health as well as physical health. Previous experiences of injustice can cause greater vulnerability to health shocks, magnifying their impacts and making recovery more difficult. Poor health, in turn, can affect a person’s state of mind, as well as their ability to achieve the capabilities that they may have reason to value doing and being.

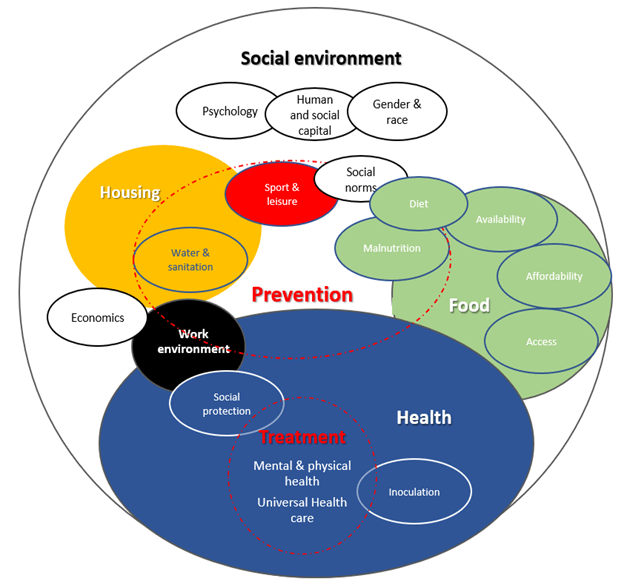

This analysis is based on a ‘socially embedded’ diagnosis of health and welfare. It reaches beyond a traditional medical model – which defines health as the absence of illness or disease, and emphasises the role of clinical diagnosis and intervention. The more holistic, socially embedded, approach is founded on the WHO’s definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. This emphasises the biopsychosocial model of health, thus including physiological, psychological and social factors, as well interactions between them.

As represented in the figure above, these health factors are affected by an individual’s housing (living environment), what they eat (food environment), where they work (working environment), social and human constraints on livelihoods, as well as eating and leisure habits (social environment) and access to the health system itself (health environment). Collectively these can be termed the Social Determinants of Health and can be directly linked to someone’s capabilities and well-being. This recentring of focus onto the community and society implies that health interventions should reach beyond the medical sphere.

To read the full report, please download to the link above.